.

Dockyard & Industry

HMS Defence was the flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot's

First Cruiser Squadron at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. She was sunk,

with her crew of 900. Nearly a century later, in 2000, divers located and

filmed her wreck.

Shipbuilding was the town's principal industry for more than a century.

Here, dwarfed by their creation, Pembroke Dock shipwrights stand below

HMS Defence on the eve of her launch (1907). Next day, she slides

gracefully into the water.

Pictures by courtesy of: shipwrights, Pembrokeshire Record Office - launch, Pembrokeshire County Council Museum Service

Pembroke Royal Dockyard

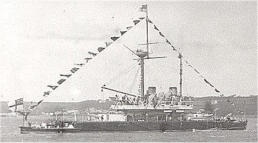

Two generations of battleships at Pembroke Dockyard. Anchored off the Dockyard is the famous HMS Thunderer, launched at the Yard in March 1872. With her Portsmouth-built

sister-ship HMS Devastation, they were the first British battleships completed without masts and sails for propulsion. The Thunderer suffered major gun and boiler explosions.

She served as Port Guardship at Pembroke from May 1895 to December 1900. Fitting out alongside Hobbs' Point is the Majestic-class battleship HMS Hannibal which had been

launched in April 1896. At 14,900 tons she was the heaviest warship ever built at Pembroke Dockyard.

We beg leave most humbly to recommend to Your Royal Highness that Your Royal Highness will be graciously pleased to establish, by Your Order in Council, the yard forming at

Pater as a Royal Dockyard.’ (1)

George, Prince of Wales, acting as Regent in place of his demented father, George III, gave the Royal Assent to this submission from the Navy Board and the Order in Council,

signed on 31 October 1815, established not only a new royal dockyard but also a new naval town.

It was an unpropitious time. Waterloo, fought on 18 June 1815, had ended the long French wars and ships by the hundred were returning home to pay off. The existing Royal

Dockyards had now more than enough capacity to support the much reduced peacetime Royal Navy. Pater Yard, however, had existed de facto for some years and its first two

ships were well advanced (2). The Navy Board had committed public funds to the county twice in a decade and was no doubt reluctant to abandon its investment. The Order in

Council served to regularise what had begun as a wartime expedient down the harbour at Milford.

A Royal Dockyard on Milford Haven arose from the Navy Board salvaging work from a bankrupt contractor. (3) During the long French wars the Royal Yards did not have the

resources to build large numbers of new warships, maintain the expanded fleets and cope with repair of battle-damaged vessels. Battles could not be forecast, and repair work

disrupted and delayed ship- building and increased the costs. (4)

The Navy Board therefore depended on private yards where new vessels could be built without interruption. During the Seven Years War two warships were built under contract

at Neyland. Richard Chitty launched the frigate HMS Milford in 1759, the annus mirabilis, and in 1765 Henry Bird and Roger Fisher launched the two-decker HMS Prince of Wales

on the same site. (5) The Navy Board looked to Pembrokeshire again in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, contracting with Messrs Harry and Joseph Jacob of London for

new warships to be built on the foreshore at Milford. When they failed the Navy Board completed the ships, renting the site from year to year. As ‘timber and iron could be

bought there cheaper and workmen obtained in abundance on lower terms than at any other place where ships are now generally built’, the Board proposed to buy the site and

establish a royal dockyard there. A sale figure of £4,455 was agreed with Charles Francis Greville and an Order in Council dated 11 October 1809 gave authority to buy the land

‘to be employed as a dock yard for building Your Majesty’s ships’.

Greville however had died on 23 April that year. His brother, Robert Fulke Greville, who succeeded him as a life tenant of the estate, refused to accept the price and, in

consequence, ‘we directed the Navy Board, on 3rd August 1810, to suspend the improvements then going forward on the premises, and on the 16th October 1812, finally to give

up possession of the same at Midsummer 1814’. (6) In failing to reach an accommodation with the Navy Board Robert Fulke Greville deprived Milford of its one great chance for

prosperity which was never to recur (7).

The dockyard facilities were transferred over the following few years to Government land at Pater and the last personnel finally moved out in mid- summer 1814 with the

completion of HMS Roch fort. Additional land at Pater was acquired and the first building slip and the excavation of a dry dock was put in hand.

The Board had invested wisely. The ‘yard forming at Pater’ was well- situated within reasonably easy reach of fresh timber supplies, particularly from the Forest of Dean, and by

chance, when metal replaced wood in ship- building, conveniently near the iron and steel foundries at Landore. This fortunate circumstance helped the yard’s survival in the

second half of the century. Furthermore, the nucleus of a trained workforce was available from Milford. Their numbers were considerably augmented after 1815 by the transfer

of now surplus craftsmen from other Royal Yards.

The founding fathers of Pater were thus largely, but not exclusively, new men. Most established men came from the West Country, shipwrights from ‘Plymouth Dock’ as

Devonport was known until 1823. These Devonians and Cornishmen - the Seccombes, Saunders, Tregennas, Willings, Trevennas (and later the Trewents and Treweeks) - although

of Celtic stock, nevertheless constituted the most radically distinct influx into south Pembrokeshire since the arrival of the Flemings in the twelfth century. They and their

descendants, with the people of Milford, created Pembroke Dock. (8)

The Royal Navy in 1815 was by far the most expensive single commitment of central government and the largest industrial organisation in the world. (9) With its supporting

dockyards the Navy embraced a wider range of specialist professional skills than any other single human activity. It is a matter of wonder that part of its operations should take

root in so remote a corner of the Realm and flourish for well over a century.

Pembroke Dock developed as a specialist building yard but its limited facilities denied it the established status of the Home Port dockyards which were also major naval bases

with victualling depots, rope works, block mills and other specialist facilities. Pembroke had only one dry dock, no fitting-out basins and, apart from Hobbs’ Point (completed in

1832 for the Irish packet service not the Navy) (10) and the Carr Jetty (completed in the first decade of the twentieth century), no satisfactory alongside berths for fitting-out

newly-built warships. Before the introduction of iron and steel, newly-launched wooden vessels were usually sent round to Plymouth, sometimes Portsmouth, under jury rig for

their masts to be stepped, if they were to be commissioned, or to go into ordinary. Early steam paddle warships went round to Woolwich to be fitted with their machinery. Later

in the century the large iron-hulled ships had to have their engines and boilers - and later also their main armament - installed at Pembroke, and be completed for sea,

undertaking their initial sea trials from Milford Haven. The completion of newly-launched ships was often delayed until the berth at Hobbs’ Point was vacated. However, it is

remarkable that the greatest battleships in the British Navy down to 1896 could be fitted out and completed alongside the tiny, tidal jetty at Hobbs’ Point. It was an

extraordinary feat of improvisation.

Pembroke and its champions campaigned ceaselessly for improved facilities. In mid-century the Haverfordwest and Milford Haven Telegraph (11) believed that ‘the only thing

required to make the Dockyard complete is the long talked of sea wall from the Hard across to Hobbs’ Point, thus locking in the Pill, and making it available for a steam factory,

steam basin etc for which its leeward situation. . . so admirably fits it’, which works ‘would be a culminating point from which additional sources of prosperity would spring’.

The steam basin never materialised.

Even after the opening of the railway through to the Dockyard town in August 1864, (12) Pembroke remained a frontier post. ‘Pembroke labours under the misfortune of being

300 miles from Whitehall. It is an outpost, and only visited occasionally’, commiserated the United Service Gazette in 1859, whose writer moreover considered that ‘the

increasing value and importance of Pembroke as a building yard, seems lost, in great measure on the authorities. (13)

Any praise for Pembroke, however faint, was seized upon by its champions. Pioneer historian, Mrs Stuart Peters, recalled in 1905 (14) the visit twenty years earlier of the ‘Chief

Constructor of the United States Navy’ who, she said, reported that ‘Pembroke is the first shipbuilding yard in the world’. The visitor was Naval Constructor Philip Hichborn USN;

he had written that ‘the best adapted of the British dockyards for building operations is Pembroke but having but one dock, no basins, and few shops and stores, is not a fitting-

out yard, and can only be rendered so at very great expense. Vessels built there usually go to Plymouth, Portsmouth or Chatham to complete.’ (15) Later historians of the town

have likewise accepted uncritically this opinion.

Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald, who was Captain Superintendent of the Dockyard from 1893-95, sometimes thought ‘that the Admiralty forgot altogether that there was any

such place as Pembroke Dockyard . . . our insignificant little Cinderella of a dockyard did not always get everything she asked for, especially if one of her big sisters was asking

for the same thing at the same time’. (16)

Even when the long-awaited jetty was being built out over the Carr Rocks after the turn of the century to provide a more efficient - but still tidal - alongside fitting-out facility,

The Navy and Army Illustrated was unimpressed:

It may be remarked that this interesting and valuable Naval establishment, even if it receive the additions and improvements that are so necessary, can never equal the other

dockyards in their great and special importance. They are fitted in every sense to be the efficient bases of the Fleet, not only as building and repairing establishments, but as

arsenals supplied with every requirement for the life and work of the Fleet . . A more modest role will always be that of Pembroke. (17)

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty paid their annual visits of inspection to Pembroke Dockyard but they seldom lingered. Artists of the Illustrated London News were

attracted to west Wales to sketch the launchings of only the greatest vessels. Even into the twentieth century, as the Dockyard was approaching its centenary, visiting members

of the Corps of Naval Constructors ‘never failed to suggest [to Assistant Constructor Arthur Nicholls] that Pembroke was the end of the world and the edge of civilisation’.’ (18)

Pembroke remained a Cinderella yard, a poor relation of the Home Port dockyards, and the desire for recognition, for confirmation of their worth, was a constant preoccupation

of its people.

Pembroke Dock became essentially an Admiralty rather than a naval town. The Commissioners of the Navy Board and, after 1832, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty,

influenced most aspects of public and private life outside the Dockyard walls. Within a few years of its foundation an Act of Parliament was passed ‘authorizing the

Commissioners of His Majesty’s Navy to establish a Market at the Town of Pembroke Dock. . . and to make Regulations for paving, lighting, cleansing, and good Order of the said

Town’. This was followed on 10 June 1825 with an Act enabling the Corporation of Pembroke to relinquish and convey to ‘the Commissioners of His Majesty’s Navy the Right of

Letting the Stalls, Sittings, and other Conveniences in the Market in the Town of Pembroke Dock, and the Right to the Rent, Tolls, and Fees thereof’.’ (19)

Exactly 100 years later, on the eve of the closure of the Yard, their Lordships still had a finger in every pie - almost literally. In June 1925 the Captain Superintendent was

ordered by the Admiralty to inspect the bakeries of Mr F. Rogers, Water Street, Pembroke Dock, and Mr A. Farrow, Charles Street, Milford Haven, and to report on whether they

were ‘a fit source for the supply of bread’. (20)

The Admiralty and its principal officers at Pembroke Dock filled the paternalist role carried out in other communities by the local landed gentry. The lead in founding the

National School, for example, was taken by a committee which included Captain Samuel Jackson, the Captain Superintendent, William Edye, the Master Shipwright, and other

Dockyard officers. (21) The foundation stone was laid by Mrs Edye on 26 April 1843, the launching day of the first royal yacht, Victoria and Albert, and the school was opened on

24 June the following year. (22)

The Navy also played a leading role in founding the first parish church. The land in Bush Street owned by Mr Meyrick of Bush Estate was conveyed in August 1846 through Edward

Laws, a principal officer in the Dockyard. The First Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Auckland, attended by a Marines guard of honour and accompanied by the Band of the 37th

Regiment, laid the foundation stone of St. John’s Church on Monday 21 September that year. (23)

Likewise, in subscription lists for good causes throughout the nineteenth century the names of Captain Superintendents and Master Shipwrights, rather than the local nobility and

gentry, usually headed the lists of contributors.

Pembroke’s greatest asset and the focus of her prosperity was her thirteen building slips, many more than in any other yard, and these made Pembroke Dockyard the nation’s

principal building yard for over a century. Nearly 250 warships and other vessels went down the ways at Pembroke in the 106 years which separated the launching of the little

sister frigates HMS Ariadne and Valorous in 1816 and that of the fleet oiler Oleander in 1922.

The century of Pembroke shipbuilding witnessed the most profound developments in naval design and construction as sail gave way to steam, driving paddlewheels and later

screw propellers, and wood was overtaken by iron and steel. Successive generations of dockyarders had to learn new skills. Their range and complexity increased as the

technical development of war-ships advanced apace after the introduction of steam in the 1850s and of iron a decade later. Traditional shipwright expertise slowly gave way to

the demands of metal. The rattle of the rivetting machines and the fumes from the foundries finally overtook the thud of the adze and the sweet smell of freshly planed oak and

pine.

Pembroke-built vessels ranged in consequence from the little cutters HMS Racer and HMS Starling launched together on 21 October 1829, the twenty-fourth anniversary of the

Battle of Trafalgar, to the colossal line-of-battleship HMS Howe, christened by Miss Harriet Ramsay on Wednesday evening, 7 March 1860, the last sailing three-decker built for

the Royal Navy. She was twice the size of Nelson’s Victory and, with a displacement of 6,577 tons, one of the two largest wooden steam battleships. (24)

Almost every major ship that went down the ways at Pembroke Dock represented a significant advance in naval architecture or played some remarkable part in British imperial

history. The first forty-five years saw the construction of nineteen first- and second-rates, ships which represented the culmination of the art of wooden shipbuilding. Among

these was Seppings’ Rodney, christened by Mrs Adams of Holyland on 18 June 1833, the first British two-decker to carry ninety guns or more. She was towed into action at

Sebastopol in 1854 by the Pembroke-built paddler HMS Spiteful where her broadside of 1470 lbs was employed to effect. ‘What a dose of pills for the enemies of Great Britain’,

exulted The Nautical Magazine. (25) HMS Rodney was relieved as flagship on the China Station in 1869 and paid off at Portsmouth on 27 April 1870, the last wooden capital ship

in active seagoing commission.

The Rodney was followed by Symmonds’ outstandingly successful Vanguard of 1835, with her beam of fifty-seven feet the broadest ship in the Navy and the broadest ever built in

Britain. She and the Rodney were fierce competitors in the Mediterranean where the ships were regarded as champions of two rival systems of naval architecture.

Pembroke Dockyard played a pioneering role in the development of early steam propulsion. The Tartarus of 1834 was the first of a series of paddle wheel steam vessels which

included the famous Gorgon of 1837 and which culminated with the launching by ‘the lady of Colonel Ellis, Commandant of the Garrison’, on Wednesday, 30 April 1851, of HMS

Valorous, the last paddle frigate ever built for the Royal Navy.

Throughout the 1850s the Yard produced the last of the Royal Navy’s great wooden line of battleships. The three-decker HMS Duke of Wellington was launched as HMS Windsor

Castle on 14 September 1852, the same day as the Iron Duke died at Walmer. Her name was changed in his honour a few days later. She and other big wooden liners of the

decade were converted while building to carry steam, being ‘cut asunder’ on the slips and lengthened to make room for boilers and engines. The Duke of Wellington served as

flagship in the Baltic during the Russian War.

Pembroke’s first ironclad was HMS Prince Consort, christened by ‘Miss Jones of Pantglasl, a Carmarthenshire lady’, on Thursday, 26 June 1862. She had been laid down as HMS

Triumph, a wooden screw two-decker, but was completed as a wooden ironclad carrying 4.5-inch and 3-inch iron plates. She was followed by other interim ironclads, the

Research, Zealous and Lord Clyde. The latter, with her Chatham-built sister ship the Lord Warden, were the largest and fastest steaming wooden ships, naval or mercantile, ever

built. But because unseasoned timber had been used in building her at Pembroke, the hull of the Lord Clyde soon became rotten and, known as the Queen’s Bad Bargain, she was

sold out of the Service within ten years. (26)

Pembroke, after Chatham, was the second of the Royal Yards to receive the plant required for iron hull construction. The first of the iron ships was HMS Penelope, a twin screw

corvette launched in 1867. A year later, she was followed by HMS Inconstant which remained afloat for eighty-eight years, the last Pembroke-built warship in existence. With a

speed under canvas of 13.5 knots and steaming at 16 knots she was the fastest ship in the world.

The despatch vessels HMS Iris, laid down on No 2 Slip in 1875, and HMS Mercury, laid down on the adjoining No 1 Slip the next year, were the first British warships built of steel

and their marine engines made them the fastest fighting ships in the world.

During the last two decades of the century Pembroke Yard launched a series of major capital ships, beginning with the turret ship HMS Edinburgh, launched by the Duchess of

Edinburgh in March 1882, and followed by the Collingwood (1882), Howe (1885), Anson (1886), Nile (1888), Empress of India (1891) and Repulse (1892). The final, and by far the

heaviest, battleship built in the Yard was the Majestic-class HMS Hannibal, 14,900 tons, launched on 28 April 1896.

Over the next ten years the yard produced a line of protected and armoured cruisers of ever increasing size. The 533.5-feet-long Drake of 1901, which was commanded by

Captain John Jellicoe from 1903-4, was the longest ship ever built at Pembroke. The last three armoured cruisers were the monsters HMS Duke of Edinburgh (1904), her half

sister HMS Warrior (1905), and the Defence (1907). All three fought in the First Cruiser Squadron at Jutland and only the Duke survived.

Some Pembroke ships made their names in distant waters. The little Starling surveyed Hong Kong waters under Lieutenant Henry Kellett where they are commemorated in

Kellett Island, the Headquarters of the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club (long since joined to the waterfront) and in Starling Inlet in the New Territories. (27) On the Pacific coast of

Canada, Fisgard Island and Duntze Head honour the frigate HMS Fisgard of 1819 (which itself recalls the French invasion of Fishguard in 1797), which served on the Pacific

Station from 1842 to 1846, and her Captain, John Duntze. On the same chart Constance Cove recalls the visit there on 25 July 1848 of the fourth-rate HMS Constance of 1846

which was the first British warship ever to anchor at Esquimalt, now the Canadian Forces’ main base on the Pacific coast. (28)

Pembroke ships made their mark in both the Polar regions. The Alert of 1856 sailed with the Nares Expedition to the Arctic in 1875 and wintered at Floeberg Beach, 82.24.

North, then the highest latitude ever attained by man. In Antarctica, the great 12,400-feet-high volcano, Mount Erebus, discovered by Sir James Clark Ross on 28 January 1841,

was named after his ship, the bomb HMS Erebus of 1826. She sailed in 1845 with Sir John Franklin on his ill-fated expedition to survey the North-West Passage and into history.

Many vessels from Pembroke Dockyard met violent ends. The fifth-rate HMS Thetis of 1817, carrying home a valuable consignment of gold, silver and plate from Rio de Janeiro,

was wrecked on Cape Frion in Brazil in December 1830. The big two-decker HMS Clarence, launched in July 1827 in the presence of Prince William Henry, Duke of Clarence,

became a training ship on the Mersey where she was destroyed by fire in June 1884. The following year she was replaced by the Pembroke-built three-decker HMS Royal William

of 1833 which was re-named Clarence. She too was destroyed by fire on the Mersey in July 1899. Fire also consumed that veteran of the Chinese opium wars, HMS Imogene of

1831, destroyed in the great blaze in Devonport Dockyard in September 1840.

Some ships met their ends in collisions at sea. The Amazon, one of the last timber-hulled sloops built for the Royal Navy, was lost within a year of her launching in May 1865.

She was commissioned at Devonport in April 1866 and two months later, on 10 July, she collided off Start Point with the steamer Osprey and both vessels sank. All hands were

saved. The Pembroke-built light cruiser HMS Curacoa of 1917 lost all but twenty-six of her ship’s company when she was cut in two in collision with the Cunarder Queen Mary

off the Irish coast in October 1942.

The sea also took its toll of many early Pembroke-built sailing warships which went down the ways at Pembroke Dockyard. The Cherokee-class sloops fared worst. HMS Wizard

of 1830 was lost on the Seal Bank off Berehaven in February 1859, the Skylark of 1826 was wrecked on the Isle of Wight in April 1845 and the Spey of 1827 was lost on Racoon

Key in the Bahamas in November 1840.

Other Cherokees disappeared without trace. HMS Thais of 1829 was lost on passage from Falmouth to Halifax in December 1833 and the Camilla of 1847 in September 1860 off

Japan. The composite gunvessel HMS Gnat, christened by Miss Mirehouse of Angle in the dark on 26 November 1867, was wrecked within a year when she ran aground on

Balabac Island in the China Seas on 15 November 1868. Perhaps the most tragic loss was that of the training frigate HMS Atalanta which had been launched as the Juno at

Pembroke Dock in 1844. She sailed from Bermuda for home on 1 February 1880 and foundered in the North Atlantic, taking with her 113 ship’s company and 170 young seamen

under training.

Pembroke Dockyard ships fought in most of Queen Victoria’s little wars, against recalcitrant emirs, rebellious native chiefs and omnipresent East Indian pirates. They also

fought in the great wars of the twentieth century. The first British warship sunk in the First World War was the light cruiser HMS Amphion of 1911, mined in the North Sea on 6

August 1914. The great armoured cruiser HMS Drake, christened by Mrs Lort Phillips in spring 1901, and the light cruiser HMS Nottingham of 1913, were both torpedoed. German

gunfire at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 claimed the last two armoured cruisers, the last two major warships built at the Yard, HMS Warrior of 1905 and the Defence of

1907. The Defence, flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot in the First Cruiser Squadron, blew up with the loss of old Sir Robert, one of the Navy’s fitness fanatics, and all

893 men on board. The Warrior was so badly damaged that she was abandoned and sank. The final loss in the Great War occurred a few weeks before the Armistice. The little

submarine L 10, launched in January 1918, was sunk off Texel in the following October. The last vessel launched at Pembroke, the fleet oiler Oleander of 1922, was sunk in

Harstead Bay on 8 June 1940 after having been damaged by German dive bombers during the Norwegian Campaign.

Naval histories record the battles and the glory but the high price of Admiralty was also paid in full by the men who built these great ships and by their families. The physical

hazards of working in the dockyard were many and often fatal. The Important Case Book maintained by the Senior Medical Officer in accordance with Article 190 of Home

Dockyard Regulations (29) records a long list of deaths and terrible injuries suffered by Dockyard workers. The terse clinical accounts compiled by Fleet Surgeons a century ago

and the occasional moss-covered gravestone are often the only remaining evidence of tragedy. For them there were no drums and no trumpets sounded.

Industrial injuries increased in severity and frequency upon the introduction of iron and steel after 1860 with its associated foundries, forges and machine shops. Falls from

staging on the building slips continued to claim lives and hernias were common. To these were now added burns, injuries with machinery and eye damage caused by flying

metal during rivetting. Almost every addition to the Navy List from Pembroke Dockyard was marked by a new gravestone in a south Pembrokeshire churchyard or a family cast

into penury.

The Dockyard Surgery treated all injuries and serious cases were sent on board the old fourth-rate HMS Nankin, a veteran of the Second China War, which served as the

dockyard hospital ship from 1866 to 1895 when facilities were provided on shore. The old Nankin was the end of the road for many.

The case of Samuel Ellis Ball, a fifty-four-year-old shipwright, who lies in Plot G.126 just inside the gates of Llanion Cemetery, was not untypical. On Thursday, 10 February

1881, the said Samuel was preparing the 465-ton composite gunboat HMS Cockchafer for launching. He fell from a stage at the stern of the ship into the bottom of the slip

twenty-two feet below and was taken out to the Nankin in a semi-conscious state where Staff Surgeon Henry Dawson found head, back and chest injuries and a fractured right

thigh. ‘He complained of great pain’, the Surgeon told the inquest, ‘I attended him for ten days, when he died . . the primary cause of death was concussion of the brain.’

The Cockchafer was launched at 9 am on Saturday, 19 February, by Miss Philipps of Lawrenny Castle. The ship ‘took the water beautifully, the strains of the band mingling with

the cheers of those assembled’. Just offshore, Samuel Ball in HMS Nankin was still barely alive. He died four hours later at 1pm. (30)

Even after the turn of the century life in the Yard could be a brutal business. John Lewis, aged fifty-six, Established Labourer No 595, was painting a bulkhead in the port

engine room of the new cruiser HMS Drake on 30 January 1901 when he slipped and fell thirteen feet onto the engine bearers and then into the crankpit. He fractured his skull

‘and is now totally deaf. In addition he has lost his left eye which he states occurred when building HMS Shannon on 1st May 1875’, wrote Fleet Surgeon Edward Luther. The

latter concluded: ‘His capacity to contribute to his own support is totally destroyed and is likely to be permanent’. Lewis was invalided on 16 April 1901.

The dreaded letters DD in red ink denoted the Royal Navy abbreviation for ‘Discharged Dead’, the final epitaph of many a fine fellow. William Williams aged forty-five,

Labourer No 1899, from Bush Street, had been greasing cogs in a machine in No 2 Fitters Shop on the morning of 21 May 1900 when he was caught in the machinery. He was

taken to the Surgery with a fractured skull and his right hand amputated ‘all except his thumb’. William Williams received his DD in red ink the following day.

His widow received £193 14s.lld. in compensation from the Admiralty. The following January the Admiralty informed the Captain Superintendent that in future coffins for

workmen accidentally killed in the Dockyard were not to be provided at public expense and, reported the Pembroke Dock and Pembroke Gazette, ‘have directed the Yard

authorities to recover from the representatives of the late William Williams . . . the cost of the coffin supplied’ (31)

The cost of coffins was a major outlay against which Dockyard workers had to make prudent provision. The Royal Dockyard Interment Society formed in about 1870 ‘to do away

with collections in the Dockyard’ collected weekly two pence subscriptions as an insurance against funeral costs. The scheme ‘has proved an inestimable boon to very many

families’, reported the Society’s annual meeting in April 1893. (32)

Distance from the Dockyard as well as danger when they got there was a constant problem for the Dockyarders, most of whom lived in a widely dispersed area of south

Pembrokeshire. This entailed long journeys by horse or boat for the fortunate but by foot for the many. As the paternal concern of the Admiralty included basic medical care it

added to the professional duties of the Dockyard surgeon.

This was recognised as early as 1841. An Order in Council dated 11 February, after emphasising that ‘the number of artificers and workmen has greatly increased [since 1815]

and the duty of the Surgeon has become more onerous in consequence of many of the men being obliged to reside at a considerable distance from the yard’, proceeded to ask

that the ‘exigency may be provided for by such small addition to the salary of the Surgeon as will enable him to keep a horse for the purpose of visiting his distant patients’.

His salary was duly increased from £400 to £450 a year.

The Dockyard Surgeon was still doing his rounds on horseback at the beginning of this century. In his memoirs, Rear Admiral T.T. Jeans, then a young doctor at Pembroke

Dockyard, recalls that houses in Pembroke Dock were so scarce ‘that many had to live in the villages in the neighbourhood, some as far as seven miles’. He considered that ‘the

long tramp to work and home, day after day, winter and summer, a tragedy in itself, was absolutely incompatible with a satisfactory day’s work in between’. The doctor’s

concern was, however, tempered by the tale he tells of a parson’s wife living in one of these remoter villages who, sympathising one day with the wife of a workman who had

so far to go to his work, received the unexpected and illuminating reply: ‘Well, Mum, he do rest all day’. Just how hard the men worked at the Yard will be discussed later.

It was part of Surgeon Jeans’ duties to ride around the country to visit Dockyarders who had reported sick. During the spring and at ‘potato’ time this had its lighter moments:

As I rode up a lane towards a cottage, II would see] over the hedge, the poor ‘sick’ man hoeing his ground. He would hear the horse’s hoof, look up, catch sight of me and dash

for his cottage and his bed, where after listening to a long-winded account of his ailments from his wife and hearing the thump of his boots on the floor overhead, I would find

him probably fully-dressed but minus those boots. (33)

The late Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Chatfield, who spent his early years at Pembroke Dockyard in the 1880s where his father was Captain Superintendent, recalled to this writer

how his mother ‘initiated the soup kitchen in Pembroke Dockyard the Dockyard for the men to have hot soup in the dinner hour’. The Pembroke Dock and Tenby Gazette

reported that hundreds of the ‘employees . . . live too far away to allow them to go home in the short dinner time granted and as a consequence they have to be content with

cold lunch in the middle of the day’. The soup kitchen was funded by nominal contributions from the men and from the proceeds of concerts organised by Mrs Chatfield. Over

the three years of her husband’s appointment fifty-seven gallons of soup were issued daily to 300 grateful men, a total of 17,000 gallons to 90,000 ‘diners’. Each man received

one and a half pints of soup a day at a cost of three pence a week. (34)

Launching days were the highlights of the Pembroke calendar throughout the history of the Dockyard. Their importance varied with the size of the ship which in turn

determined the rank of the lady chosen to perform the christening. ‘These events are to hundreds the "sunny spots" in their chequered existence’, commented the

Pembrokeshire Herald in its report of the launching in 1844 of the two-decker HMS Centurion by Mrs Cockburn of Rhoscrowther. (35)

The Yard was customarily opened to the public on launching days and the latter occasions attracted crowds of visitors and welcome extra trade in the town. The first launchings

were on 10 February 1816 before ‘an impressive concourse of spectators assembled to witness the novel event’. The sixth-rates, HMS Ariadne and Valorous, built together on

that first improvised slip, stem to stern, went afloat, one bows first and the other, more conventionally, stern first, ‘a circumstance which created considerable interest at the

time’. (36) The Ariadne was the last ship commanded by the novelist, Captain Frederick Marryat, whose first book, The Naval Officer, was completed on board at Plymouth.

The launch of the great three-decker HMS Windsor Castle in 1852 was typical. According to one report: ‘From an early hour on Tuesday morning conveyances of every

description commenced swarming into Pater . . . and every description of passage boat from Carmarthen, Tenby, Haverfordwest and Milford and other places, lent their aid in

conveying to the scene some of the thousands who, throughout the day, thronged the neighbourhood of the Dockyard.’ (37)

At the other end of the scale the little flat iron gunboats HMS Tickler and Griper, launched on Monday, 15 September 1879, were christened by two little girls, Miss E.J. Warren,

daughter of the new Chief Constructor, and Miss H.M.F. Powell, the six-year-old daughter of Pembroke Dock’s second Vicar and former naval officer, the Rev. F.G.M. Powell, of St

John’s Church. ‘Each young lady’, ran one press report, ‘was presented with an elegantly polished mahogany boxes (sic), lined with blue velvet, containing a burnished

miniature steel axe, with which each young lady used to sever the cords suspending the weights over the dogshores.’ (38)

The launching process was a complicated engineering undertaking and was not always a success. The launch of the ninety-gun screw two-decker HMS Caesar in the summer of

1853 took seventeen days round-the-clock effort. Lady Georgiana Balfour, daughter of the Earl of Cawdor, christened the 2,767 tons ship on Thursday, 21 July, but the vessel

stopped after sliding only half her length down the slip. ‘Nothing could equal our consternation’, wrote Captain Sir Thomas Pasley, the Captain Superintendent, in his diary, ‘No

one could guess the cause.’ (39) When the tide ebbed the ship’s bilgeways and stern were found embedded in the mud with fifty-six feet of the hull suspended without support

over the groundways. The operation mounted over the next seventeen days to free the ship became an epic and was fully reported in the Pembrokeshire Herald. On the

following day ‘all the casks of the town were borrowed and it was gratifying to see the alacrity with which these were furnished by publicans and others - the former in some

instances actually emptying both beer and porter into tubs and vats’.(40) The tide rose more quickly than expected next day, Sunday, and the Dockyard bell was rung and ‘the

(Dockyard] Battalion drums sent through the town - beating to quarters, and messengers on horseback and foot sent off in all directions’. Improvisations failed and it took

specially-built camels lashed beneath her counter at low water on Friday, 5 August, to move her. Across the weekend the ship moved forty-eight feet. Then, at 6.10 on Sunday

evening, two hours before high water, she started to move. The Battalion drums again ‘paraded the town . . . the church and chapels etc were soon deserted’.41 Sir Thomas

Pasley recorded: ‘And at length she came and marvellous was the excitement and loud and long were the cheers of our men who, poor fellows, have worked as hard as men

could work’.(42)

The cause was long debated. Local tradition held that a local witch, excluded from attending the launching, put a curse on the Caesar. More likely there was insufficient tallow

between the sole of the ways and the launching slip and the sliding surfaces had been planed too smoothly.(43)

The launching of minor vessels, too, could prove disastrous on the day. The little 238-ton screw gunboats HMS Janus and Drake were built on the same slip sharing one set of

bilgeways. They were christened at 5.30 pm on Saturday, 8 March 1856, by Mrs Mathias of Lamphey Court, wife of the High Sheriff, from staging erected on the side of the slip

between the two vessels. Both hulls moved off together, Drake leading. As the Janus passed she demolished the platform and Mrs Mathias and her children were ‘whirled out of

their place’ and ‘hurled with frightful violence’ into the slip. In the confusion ‘the gallant little vessels went off without a single cheer or other symptom of approbation’. Miss

Mathias, with a broken collar bone, ‘was for some time insensible’, but they all survived. A week later Mrs Mathias, ‘being deeply sensible’ of the workmen’s help in rescuing

her family ‘from the confusion and entanglement into which they were cast’, rewarded them each with ten shillings.(44)

Victoria and Albert II and III, two generations of

Royal Yachts, at Pembroke Dock in 1899.

HMS Thunderer, launched 1872, later

Pembroke Dockyard's guardship

Much more calamitous was the accident to the new royal yacht Victoria and Albert in the winter of 1900, an event which seriously damaged the professional reputation of

Pembroke Dockyard and ruined the career of the ship’s designer, the Director of Naval Construction, Sir William White.

The 380-foot steel yacht was laid down in December 1897 as a replacement for the veteran paddle yacht of the same name which had been built at Pembroke Dockyard nearly

fifty years earlier. The new vessel, the last ship to be launched from Pembroke Yard in Queen Victoria’s reign, was launched by the Duchess of York (later Queen Mary) on 9 May

1899.

After her engines and boilers had been installed and her masts stepped under the sheerlegs at Hobbs’ Point, the berth had to be vacated for fitting out the new cruiser HMS

Spartiate. As there was no other jetty (Pembroke’s limitations again!), the yacht was put into dry dock for completion. This was not an unusual proceeding but it led to disaster.

The completed yacht was to be floated out of the dock at dawn on 3 January 1900. As the dock flooded the ship slipped to starboard off her blocks aft with a list of eight

degrees to port. ‘The Marine guard immediately sounded the bugle call’ and all ports and scuttles were closed.(45)

The caisson could not be secured at high tide allowing much of the water to escape, leaving the ship unsupported, despite the efforts of the Dockyard fire brigade pumps. Sir

William White, summoned from London, arrived at 2 am on ‘the bleak dock-side and saw the beautiful thing heeled over with naptha flares burning all round, a host of men

climbing over her and shouting angrily’. He felt the hostility in the air but was generous in his praise of the emergency measures which had been taken. ‘It is not possible for me

to over- state the value of the prompt and skillful action of the Dockyard officers’, he wrote, ‘to which we owe the rescue of the vessel from a dangerous position.’ (46)

The yacht was safe and watertight with damage limited to an 8-inch dent running over twenty-five feet amidships. She was ballasted with 200 tons of water and 105 tons of pig

iron before the next tide, when she was floated out with a ten degree list and taken to a buoy where, on 4 January, Sir William conducted stability tests using a team of 475 men

rushing from side to side.

There was a subsequent furore in Press and Parliament. An enquiry presided over by Mr G.J. Goschen, First Lord of the Admiralty, reported on 29 April. The accident was due

‘not to a single error or miscalculation in the general design but to an excess in weight and equipment [771 tons] distributed over a number of items’. In short, the ship was top

heavy. (47) Sir William was formally censured by the Admiralty and retired a broken man. (48)

The hierarchy of the Royal Dockyards was as strictly determined as the Royal Navy which they served. At the head was the Commissioner or, after the absorption of the Navy

Board by the Admiralty in 1832, the Superintendent - a rear admiral in the major yards but a captain at Pembroke Dockyard. He commanded in all respects: ‘Commissioner -

head of the yard - great man - remarkably great man’, was the accurate description by Arthur Jingle in Pickwick Papers of the Commissioner at Chatham where Dickens’ father

was employed. These sea officers had no shipbuilding knowledge and there was often tension between them and their civilian Master Shipwrights, later Chief Constructors, who

had spent a lifetime in the trade. These senior captains, however, knew about handling men.

Pembroke had thirty-five Captain Superintendents between 1832 and 1926 who were borne on the ships’ books of the successive guardships at Pembroke which they formally

commanded. They were a mixed lot but all great characters. The first two were Trafalgar veterans. Sir Charles Bullen, who formally commanded the old Royal Yacht Royal

Sovereign off the Yard, had been Flag-Captain to Rear Admiral The Earl of Northesk, third-in-command, in HMS Britannia. His successor, William Pryce Cumby, had been First

Lieutenant of HMS Bellerophon at the battle and had taken command from the mortally wounded Captain John Cooke: ‘Tell Cumby never to strike!’, cried the dying Captain.

(49) Cumby was the senior captain in the Royal Navy when he came to Pembroke but he died in post in 1837.

Another veteran of the French Wars, Watkin Owen Pell (Superintendent 1842-45), had lost his leg in a gallant frigate action in 1800. He is said to have spied with a telescope on

his men from Barrack Hill and his donkey, on which he toured his domain, was trained to carry him up the gangways onto the decks of ships under construction. (50)

Pembroke, despite its secondary status, was a sought-after appointment. ‘I shall always look back on Pembroke Yard as the most comfortable and satisfactory epoch of my

life’, wrote Sir Thomas Sabine Pasley (1849-54) in his diary. His daughter, Louisa, recalled: ‘Pembroke Dockyard was.. . a paradise to the Captain Superintendent. No telephone

disturbed his equanimity or harassed his clerks. The railway did not approach within 40 miles at the date of his taking up the appointment though it had advanced to only ten

miles when his time expired.’ Old Sir Thomas, wracked by money worries, was cheered by the Dockyard workers and sailors from the guardship HMS Saturn when he left in the

Pros pero steamer on 5 June 1854: ‘At last the Yard was cleared’, he wrote, ‘and the last sound of Pembroke Dockyard that I shall ever hear died away. But the recollection will

never die from my memory. I was quite overcome and felt it all very deeply . . . God bless them all!’ (51)

Forty years later Pembroke was no less attractive. That tough old sailorman and harsh disciplinarian, Admiral Charles ‘Rough’ Fitzgerald, came to the Yard in 1893:

Their Lordships... appointed me to the very best captain’s appointment in the Service . . Superintendent of Pembroke Dockyard . . . and a delightful two years it proved to be.

A good home, an excellent garden, a nice compact little dockyard a good long way from London and the Admiralty, and the kindest and most hospitable neighbours I have ever

come across. (52)

The Captain Superintendents at Pembroke were a colourful lot. Their reign of nearly a century in west Wales came to a close with AFO (Admiralty Fleet Order) 1477 dated 4

June 1926: ‘As Pembroke Dockyard will be reduced to a care and maintenance basis by 31st May. it has been decided that the appointment of Captain Superintendent is to

terminate on that date’. On that last day of May the 35th incumbent, Leonard Donaldson, wrote to his staff: ‘I wish you all every good luck and trust that the Yard may before

long be used for some useful purpose and bring some help to the Town and District’. (53)

These Dockyarders were a gallant band. The Devonport Dockyard historian, George Dicker, considered that ‘Pembroke Dockyardsmen . . . brought the conscientious devotion

and pride of achievement of the countryman to the art of shipbuilding. Tough to a degree unheard of today they worked hard and earned for themselves a nationwide

recognition of their skill and ability.’ (54)

They were certainly proud of their connection with the Yard; many gravestones throughout south Pembrokeshire and further afield include among their inscriptions the proud

association ‘late of Pembroke Dockyard’ or ‘of Her Majesty’s Royal Yard at Pembroke’. (55)

Dicker accurately reflects the Pembrokians’ pride but overstates their devotion. There is nothing to suggest that Pembroke men were any slower than their colleagues in other

royal Yards in seeing off Their Lordships. Indeed, Surgeon Jeans was of the opinion that the well-known ‘dockyard crawl’ was more apparent in Pembroke Dockyard than in any

of the other three great dockyards, and that even the Dockyard shire horses adapted themselves to it:

A couple of these splendidly conditioned animals might be seen drawing, painfully and slowly, a small empty lorry, but at the first sound of the dinner bell, the drivers would

slip off their harness and away they would go, helter skelter across the pieces of waste land, jumping the low chain railings in between, frisking like colts, each trying to get to

the harness shed and his feed before the others. I often went out into the Yard simply to watch this horse play - and some sign of active vitality. (56)

Captain Burges Watson, Captain Superintendent just before the turn of the century, was convinced that his workforce was idle and his suspicions reached dramatic climax on 15

July 1898, when he assembled every Dockyard officer from Chief Constructor down to the humblest chargeman in the Dockyard Schoolroom. He reported that he had found a

hutch in a timber stack, roofed with corrugated iron, and equipped with towels, water and pillows and in which, it seemed, men had been going to skulk, sleep and - worse still

- perhaps smoke, for weeks or months previously. The Dockyard Police had later found three men in there and he had discharged them. A few days earlier he had been on board

the cruiser HMS Andromeda when, at five minutes to Noon, he had distinctly heard the sound of a bell, not the official bell, but a hammer striking on a shackle, and

immediately afterwards nearly all hands ceased working. There were other examples of shirking. He had come ashore at the landing stage one night in plain clothes and noted

that there was no sound of activity on board the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert where the night shift was on overtime but that when he got near ‘a perfect din’ was set up.

Of course, this all caused a great uproar in the local newspaper with complaints that 2,200 men should not be tarred with the same brush as three errant skulkers. (57)

The workforce was a close-knit community which any senior naval officer found almost impossible to penetrate. Surgeon Jeans observed that the workmen through inter-

marriage over long years had become so closely inter-related that ‘it was no uncommon thing to find a gang of riggers or shipwrights whose foremen and timekeepers were the

fathers or uncles or brothers of most of the gang’. They must have led the Captain Superintendents a merry dance.

The decline of Pembroke Dockyard began soon after the turn of the century. This was not evident to the men then employed. The armoured cruiser HMS Defence, launched in

1907, was the last major warship built at the Yard. Thereafter only light cruisers - averaging one a year - and a handful of submarines occupied a few of the slips which

throughout the Great War were concerned with war repair work.

The future United States President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, visited Pembroke Dockyard in July 1918 when he was Assistant Secretary of the (US) Navy. He thought Pembroke was

‘an old, small affair somewhat like our Portsmouth Navy Yard’. In a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniel, Roosevelt reported: ‘It has been expanded since the

War from 1,000 to nearly 4,000 employees, and does mostly repair work to patrol vessels etc, and is also building four submarines. I was particularly interested to see over 500

women employed in various capacities, some of them even acting as molders’ helpers in the foundry, and all of them doing excellent work.’ (58)

It was somewhat prophetic of future developments in the harbour that the very last vessel launched at Pembroke should have been an oil tanker. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary

Oleander, named by Mrs Dutton, wife of the Captain Superintendent, went down the ways on Wednesday evening, 3 May 1922. As she entered the water ‘a loud cheer was raised

by all present’. (59) It must have been a pale shadow of the great launching days the Dockyard had seen. She was brought alongside the Carr Jetty, that first class fitting-out

jetty - the lack of which had hindered fitting-out operations for half a century - but which had come too late.

The home dockyards were all now seriously under-employed. The machinery and boilers for the Oleander were made at Devonport, Portsmouth and Chatham, ‘the work having

been distributed for the purpose of keeping workmen in the several engineering departments at those dockyards in employment’.

The following month the Dockyard suffered a terminal injury with the burning down of the mould loft. Various newspapers reported the tragic event. ‘Practically the whole

population of the town came to witness what was, in many respects, a wonderful spectacle.’ A north-westerly breeze fanned the fire ‘which consumed, not only the

constructive centre of the Yard, but its archives and collections of ship models and figureheads’. The best efforts of the Metropolitan Police, ship’s company of the light cruiser

HMS Cleopatra in refit, and two companies of the York and Lancaster Regiment, were in vain. The serious fire . . . would have been regretted at any time, but happening just

now, when the future of the Yard is in doubt, it can only be regarded as a first class calamity. The towns of Pembroke Dock, Pembroke and Neyland, with many adjacent

villages, are entirely dependent on the Government Dockyard, and the heavy reduction of workmen employed, ranging from 4,000 to a matter of 1,700, has materially

contributed to the attenuated resources of the whole district. (60)

The long and vigorous campaign to save Pembroke Dockyard has been ably documented elsewhere. (61) A petition to Prime minister Stanley Baldwin stressed the lack of

alternative employment and the economic consequences. The town would be denuded of wage earners with the transfer of 400 established men and the discharge of 800 hired

workers for whom there was no other work; trade would be paralysed and there would be bankruptcy and ruin for traders; homes would be broken up and family ties severed.

The decision, however, was irreversible. The Navy simply had too many dockyards and the Admiralty had to keep a fleet together with much-reduced funds. Pembroke and

Rosyth had to go. The choice was laid out starkly by the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty, in his speech at The Lord Mayor’s Banquet on 9 November 1925:

‘Whether these Yards are necessary for naval purposes, the Admiralty is the only competent judge. As to whether they are necessary for political or social reasons is for the

Government to decide. The fact is, that so far as the upkeep of the Fleet is concerned, they are entirely redundant.’ (62)

Pembroke Dock is now ‘almost entirely a town of unemployed and pensioners’, commented the Telegraph Almanack in 1927. The direct consequence of State policy was thus to

destroy a town: between 1921 and 1931 some 3,500 people, a quarter of the town’s inhabitants, migrated, while in 1937 over half of the insured population of the borough

were unemployed. (63) It is now apparent that in its heyday things had been very different. Growth had continued fast down to the close of the nineteenth century, the

Pembrokeshire Herald of 20 January 1899 observing: ‘prospects for the future of the Yard are bright’; it pointed out that very recently there had been only about fifty joiners in

the Yard, whereas at the present time the number was 200. If we turn to the total numbers employed, then we discover that on 1 May 1860 some 1,356 worked there, a number

which grew to between 2,200 and 2,500 by 1898~1899. (64) Wages were high compared with those of other workers: thus the average weekly wage of skilled labourers in the

Yard in September 1899 was 24s. whereas the annual average weekly wage in 1898 for those Pembrokeshire farm labourers who were married and provided their own food was

15s. lOd. (65)

There is no mistaking the calamity of 1926 for Pembroke Dock inhabitants. But a good many employed in the Dockyard, we have seen, lived in Pembroke, Neyland. and in

outlying villages like Llangwm, many from the country districts having been formerly employed as farm labourers. Some of the Dockyard mechanics and artisans living in these

outlying rural villages rented smallholdings - a reminder once again that Pembrokeshire workers employed in industrial undertakings often had links with the land. (66) These

neighbouring towns and villages also suffered in 1926. Local farming, too, was adversely affected through the loss of demand for its produce from dockyard workers and their

families. And, as the later chapter on Leisure and Recreation will show, local sport suffered through young men migrating from the district.

On 4 April 1956 the hulk of the old iron screw frigate, HMS Inconstant, which Lady Muriel Campbell had ‘gracefully and dexterously [sic]’ launched at Pembroke Dockyard on a

Thursday afternoon in 1868, arrived at a Belgian port for breaking-up. She was the last Pembroke-built ship afloat. On 29 June that year, Admiral Leonard Andrew Boyd

Donaldson, the last Captain-Superintendent of Pembroke Dockyard, died aged eighty-one in a Portsmouth hospital. The last ship and the last sailor had gone to their haven

under the hill just thirty years after the closure of His Majesty’s Royal Yard at Pembroke Dock.

Today almost nothing remains of those former glories. The building slips have almost all disappeared beneath new developments. A few surviving Dockyard offices, priceless

examples of the stonemason’s art, are slowly crumbling. The old Dockyard Chapel has been stripped of its memorial window to the lost Atalanta, its oak pews were taken away

by the Royal Air Force and its famous bell, captured from the Spaniards, gone without trace. (67) Nothing survived. No pubs are nanted Duke of Wellington or Drake, Hannibal or

Howe. The origins of Melville Street, Clarence Street, Cumby Terrace and Laws Street are known to the few and never taught in the schools. Even the grave in the old Park

Street Cemetery of Captain William Pryce Cumby was destroyed by Pembroke Borough Council. Old Cumby, ‘Tell Cumby never to strike!’, deserved better. The decay cannot,

however, dim the achievement. Ruskin wrote fervently:

For one thing this century will in after ages be considered to have done in a superb manner and one thing I think only. . . it will always be said of us, with unabated reverence,

"They built ships of the line" . . . the ship of the line is [man’s] first work. Into that he has put as much of his human patience, common sense, forethought, experimental

philosophy, self control, habits of order and obedience, thoroughly wrought handwork, defiance of brute elements, careless courage, careful patriotism, and calm expectation

of the judgement of God, as can well be put into a space of 300 feet long by 80 broad. And I am thankful to have lived in an age when I could see this thing so done. (68)

References

1 ) Order in Council, 31 October 1815.

2 ) Ibid.

3 ) J.F. Rees, The Story of Milford (Cardiff, 1954).

4 ) B. Pool, Navy Board Contracts 1660-1832: Contract Administration under the Navy Board (1966), p. 86; Id., ‘Some Notes on Warship Building by Contract in the

Eighteenth Century’, The Mariner’s Mirror 49, 2 (May 1963), pp. 105-09.

5 ) Gent. Mag. xxxv (June 1765), p.294.

6 ) Order in Council, 31 Oct. 1815.

7 ) For a detailed account of naval shipbuilding at Milford, see Rees, op.cit., pp. 25-42.

8 ) Many were Cornish Methodists - see C. Mason, Pembroke Dock, Pembroke Dockyard and Neighbourhood (Pembroke Dock, 1905), p.157 and Peters, Pembroke Dock,

p.159.

For a scholarly article on Richard Tregenna, see J. Armstrong, ‘Then and Now’ in the Western Telegraph, 14 Dec. 1988.

9 ) J. Coad, The Royal Dockyards 1690-1850 (Aldershot, 1989), p.ix.

10) C. Dicker, ‘The Neglected Dockyard’ (unpublished manuscript, 1971), pp.7-8; Peters, op.cit.,pp. 32-3.

11) H and MHT. 28 May 1856.

12) M.R.C. Price, The Pembroke and Tenby Railway (Oakwood Press, Oxford, 1986), pp.18,31; Peters, op.cit., p.45.

13) United Services Gazette, 12 Nov. 1859.

14) Peters, op.cit., p.27.

15) Report on European Dockyards by Naval Constructor Philip Hichborn, United States Navy (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1886). 49th Congress 1st

Session. House of Representatives Misc. Doc. No.237. See also Report by Chief Engineer I. W. King USN on European Ships of War . . . Dockyards etc. (Washington,

1877). 44th Congress 2nd Session. Senate Ex. Doc. no.27, p.246.

16) C.C. Penrose Fitzgerald, From Sail to Steam (1916), p.198.

17) J. Leyland, ‘The Royal Dockyards. Pembroke Pt. 1’, Navy and Army Illustrated (20 Dec. 1902).

18) Arthur Nicholls, ‘They built Ships of the Line’ (unpublished manuscript autobiography in the Ministry of Defence Whitehall Library, c.1946).

19) 59 Geo 3 c 125 (authority to establish market); 6 Geo 4 c 36 (Borough of Pembroke relinquish and convey to Navy Board right of letting stalls etc); 2 and 3

Williams 4 c 40 (property vested by 6 Ceo 4 c 36 transferred by Navy Board to Admiralty).

21) Director General, Medical Department, Admiralty LN 1653, dated 25 June 1925, to Captain

Superintendent, HM Dockyard, Pembroke. Surgeon Commander R.B. Scribner reported to the

Captain Superintendent on 6 July both ‘to be quite suitable and fit’. Copies in author’s possession.

21) Peters, op.cit., p.110 (but Captain Samuel Jackson had been succeeded by Captain Watkin Owen Pell by the time of the bazaar in September 1842).

22) Dates taken from National School commemorative medallion in author’s possession.

23) Peters, op.cit., pp. 85-7.

24) When HMS Howe was dismantled in 1921 her timbers were used to build Liberty’s in Regent Street, London. The company has preserved her figurehead, a bust of

Admiral ‘Black Dick’

Howe.

25) The Nautical Magazine ii (1833), p.492.

26) 0. Parkes, British Battleships (1956), p.94.

27) The name is unlikely to survive the reversion of the colony to the People’s Republic of China in 1997.

28) J.T. Walbran, British Columbia Coast Names 1592-1906. Their Origin and History (Ottawa, 1909); B.M. Gough, The Royal Navy on the Northwest Coast of North

America 1810-1914 (Vancouver, 1971); Lawrence Phillips, ‘An Interesting Frigate from Pembroke Dockyard. HMS Constance of 1846’, The Mariner’s Mirror 73, 1(Feb.

1987), pp. 61-9.

29) Home Dockyard Regulations, 1904, p.58.

30) PD and TG, 10, 24 Feb. 1881.

31) PD and PC, 17 Aug. 1900, 25 Jan. 1901.

32) Ibid., 13 April 1893, 28 June 1901.

33) T.T. Jeans, Reminiscences of a Naval Surgeon (1927), pp. 123-30.

34) Letter to the author from Lord Chatfield, 9 Dec. 1959; see also Chatfield, The Navy and Defence (1947), p.18; PD and TG, 22 Feb. 1883, 6 Nov. 1884, 5 Nov., 3

Dec. 1885.

35) PH, 3 May 1844.

36) H and MHT, 3 Oct 1855.

37) Illustrated London News, 18 Sept. 1852.

38) PD and TG, 18 Sept. 1879.

39) Sir Thomas Sabine Pasley’s personal diary; Louisa M. Sabine Pasley, Memoir of Admiral Sir Thomas Sabine Pasley (1900), ch. xiv; Lawrence Phillips, ‘Captain Sir

Thomas Sabine Pasley Bt RN and Pembroke Dockyard’, The Mariner’s Mirror 71, 2 (May 1985), pp. 159-65.

40) PH, 29 July 1853.

41) Ibid., 12 Aug. 1853.

42) Pasley diary.

43) W. Robinson, ‘On Completing the Launching of Ships which have stopped on their Launching Ways’, Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects xii (1871).

44) H and MHT, 12, 19 March 1856; PH, 14 March 1856.

45) PD and PG, 5 Jan. 1900.

46) F. Manning, The Life of Sir William White (1923), pp. 418-40.

47) Admiralty. Report of the Committee appointed by The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to enquire into the circumstances which led to the accident to the

new Royal Yacht at the time when the vessel was undocked at Pembroke (29 April 1901); C. M. Gavin, Royal Yachts (1932), App. vi; ‘Walrus’, ‘Royal Disaster’, Naval

Review xlvi, 4 (Oct. 1958), pp. 437-42.

48) Sir William White had known Pembroke Dock in happier days. When employed on building the

battleship HMS Dreadnought at the Yard thirty years earlier he had become engaged to Alice, younger daughter of Richard Martin, the Chief Constructor. The couple

married at St. John’s Parish Church on 4 August 1875. It was a long and happy marriage.

49) C. Pengelly, The First Bellerophon. A Famous Ship of the Royal Navy (1966).

50) Peters, op.cit., p.147.

51) Pasley, Memoir; Pasley diary.

52) Fitzgerald, op.cit., p.198.

53) Addressed to ‘All Departments’ and dated 31 May 1926. Copy in the author’s possession.

54) Dicker Manuscript, ch.1, p.2.

55) Such as the grave of Edward Laws, the longest-serving Principal Officer at Pembroke Dockyard, who died on 2 January 1854. He and his wife were buried in the

catacombs at Kensal Green in London.

56) Jeans, op.cit.

57) PD and PG. 22 July 1898.

58) M. Simpson, Anglo-American Naval Relations 1917-1919 (Naval Records Society, 1991), p.163.

59) PCG, 5 May 1922.

60) PH, 30 June 1922; PCG, 30 June 1922; Ward-Davies’ Free Press, 30 June 1922; PT, 28 June 1922.

61) A.D.B. Tilbury, WWG, 6 Sept. 1957 to 1 Nov. 1957.

62) W.S. Chalmers, The Life and Letters of David, Earl Beatty (1951), p.469.

63) D. Thomas, ‘Economic Decline’, in T. Herbert and G.E. Jones, eds., Wales Between the Wars (Cardiff, 1988), p.16.

64) PH, 20 July 1860, 20 Jan. 1899.

65) Ibid., 15 Sept. 1899; Employment in Agriculture, 1919, p.108.

66) PH, 24 Nov. 1899; Welsh Land Commission, 1893-96, Evidence, ii, Qs. 29130, 31062.

67) The bell was taken from the Spanish second-rate Fenix captured during Rodney’s

Moonlight Battle on 16 January 1780. The ship was commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Gibraltar and was broken-up at Pembroke Dockyard in November 1836

when, presumably, her bell was mounted in the recently-completed Dockyard Chapel.

68) John Ruskin in Thomas J. Wise, ed., The Harbours of England (Orpington, 1895), pp.24-5.

Pictures by courtesy of: two generations of battleships, cruiser, c. 1900, HMS Drake, HMS Thunderer, two generations of Royal Yachts, shipwright, Tenby Museum and

Art Gallery - Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert III, Pembrokeshire County Council Museum Service - HMS Erebus, Pembrokeshire County Libraries.

by Lawrence Phillips, Vice-President, The Society for Nautical Research.

Text from Commander Phillips' chapter on Pembroke Yard published in the Pembrokeshire County History Vol IV, Modern Pembrokeshire, and reproduced

by courtesy of the author and the Pembrokeshire Historical Society.

TOP

HOME

(Amendment, updates and additions) (AJ) Anndra Johnstone

This site is designed, published and hosted by CatsWebCom Community Services © 2018 part of Pembroke Dock Web Project